Most “possessory” offenses in Philadelphia occur in “high crime” areas of the city. Unfortunately, many police officers believe that the higher the crime rate in a particular section of the city, the more leeway they should have to intrude upon the privacy of private citizens. Many of my clients are stopped and harassed by police multiple times a day for no lawful reason, and so are many others in their neighborhoods. Typically, police don’t even report these “encounters”. It’s only when contraband is found that police need to justify their actions, and while officers often embellish the facts to justify a stop, they are often surprised at how exacting the standards of “reasonable suspicion” and “probable cause” can be after a motion to suppress is litigated.

Questionable Search and Seizure

One such case played out in the Philadelphia courts last week. In that case, police were conducting a narcotics surveillance in yet another “high crime” neighborhood. From a confidential location, they observed the target of their investigation make several drug transactions. The suspected buyers were stopped a distance away and police confirmed those individuals had narcotics on their person. At no time did the police observe my client, M.H. engage in any transactions with the suspected buyers, or with the target. However, towards the end of the surveillance M.H. was observed walking over to the target and pointing in several directions. There were no police visible at this point, but the investigating officer testified that he thought it was possible that M.H. had discovered the surveillance and had compromised it by informing the target. M.H. then ran through the lot below:

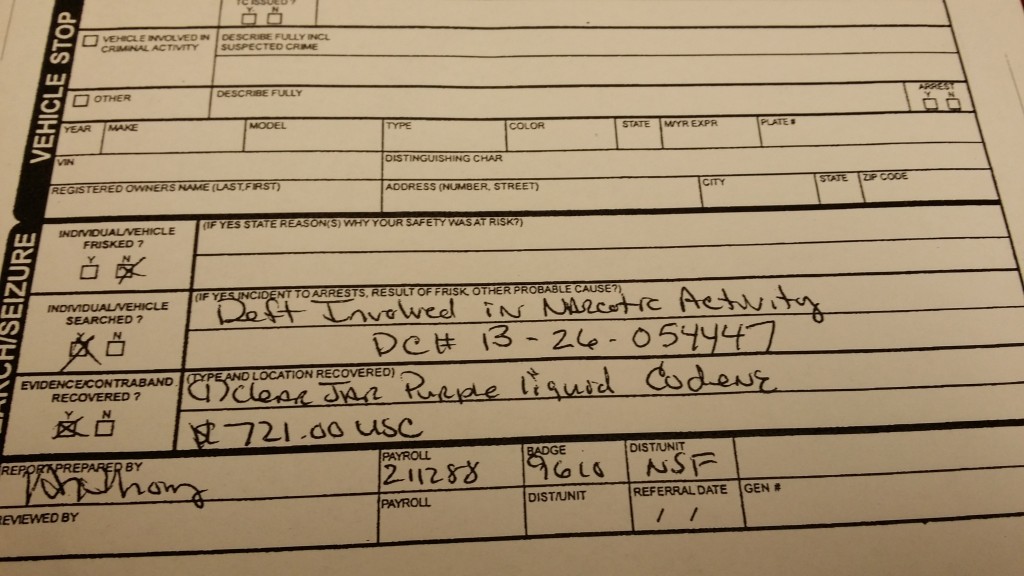

M.H. ended up in a nearby house and police followed him into the house and apprehended him. After being searched, police found a bottle of liquid codeine and $721.00. He was charged with illegal possession of narcotics, but not for conspiracy to deliver narcotics with the target.

Although M.H. disputed some of the facts, the decision was made to pound on the law rather than the officer’s credibility. In cases such as this, where the cops could have made the facts much worse for M.H. if they wanted to, credibility arguments to a judge can be tough. (However, many cases do boil down to credibility, and future blog posts will demonstrate how cases can be won on that basis as well.)

Motion to Suppress Evidence

At the motion to suppress evidence the officer had a difficult time articulating why the decision was made to stop and search M.H. This may be due to poor training and/or a belief that anyone in a high crime area with even tangential contact with a narcotics investigation can be stopped. The officer attempted to base the stop and search in this case on the conversation between the target and M.H., the pointing around, the fact that this occurred in a known drug area, and the “flight.” However, the PA Supreme Court has held that mere presence in a high crime area does not give rise to reasonable suspicion to stop, let alone probable cause, nor does conversing with known drug addicts or dealers. The PA courts have also held that mere flight does not give rise to probable cause, and of course in this case, it could not even be established that M.H. knew of the police presence and was therefore fleeing from them.

Arguably, the totality of the circumstances gave the officers reasonable suspicion to stop and investigate M.H. However, under the law, even if there is reasonable suspicion, there still must be articulable facts presented that the officer believed he was armed and dangerous before conducting a search. PA courts have held that the mere fact that drugs are possibly involved does not give rise to the presumption that the individual is armed thereby justifying a “Terry frisk” for weapons. During the motion, knowing that there was probably not enough evidence to justify a full-fledged search, the prosecutor used leading questions to get the officer to testify that the drugs in this case were recovered pursuant to a “Terry frisk” under the less stringent analysis of “reasonable suspicion.” On cross examination, the officer was presented with the following document that was prepared after the arrest of M.H.

Rather than attach the officer’s credibility, he was asked whether the document refreshed his memory as to whether M.H. was “searched” pursuant to an arrest or “frisked” for officer safety. Grateful for not having his credibility questioned and perhaps peeved at the prosecutor for walking him into a trap, the officer was more than helpful to the defense with his testimony for the duration of the hearing. Since a “search” cannot precede an arrest, and M.H. was not arrested for any of his actions prior to the recovery of the drugs from his person, the Judge properly suppressed the evidence in this case. While I give kudos to the officer in this case, hopefully some of the officers in the audience got a lesson on how and when a person can be lawfully stopped and searched, and will be deterred from violating the rights of innocent people in the future. Unfortunately, my guess is that a few of them merely picked up a few pointers on what they need to put in their reports to justify their illegal actions.